How Sweet & Beautiful It Is…

British poet Wilfred Owen fought in the First World War; his poems were all written in the span of a year before he was killed in action at the age of 25. Perhaps his most famous poem is titled Dulce et Decorum Est, which highlights the contrast between one moment of war to the wider narrative that is told of war:

Bent double, like old beggars under sacks,Knock-kneed, coughing like hags, we cursed through sludge,Till on the haunting flares we turned our backs,And towards our distant rest began to trudge.Men marched asleep. Many had lost their boots,But limped on, blood-shod. All went lame; all blind;Drunk with fatigue; deaf even to the hootsOf gas-shells dropping softly behind.\\Gas! GAS! Quick, boys!—An ecstasy of fumblingFitting the clumsy helmets just in time,But someone still was yelling out and stumblingAnd flound’ring like a man in fire or lime.—Dim through the misty panes and thick green light,As under a green sea, I saw him drowning.\\In all my dreams before my helpless sight,He plunges at me, guttering, choking, drowning.\\If in some smothering dreams, you too could paceBehind the wagon that we flung him in,And watch the white eyes writhing in his face,His hanging face, like a devil’s sick of sin;If you could hear, at every jolt, the bloodCome gargling from the froth-corrupted lungs,Obscene as cancer, bitter as the cudOf vile, incurable sores on innocent tongues,—My friend, you would not tell with such high zestTo children ardent for some desperate glory,The old Lie: Dulce et decorum estPro patria mori.

The last lines are a Latin saying that was often quoted at the start of WWI. The translation: “How sweet and right it is to die for your country.”

“War is Beautiful”

In War is Beautiful, David Shields takes up Owen’s theme, carefully curating photos from the cover the New York Times to illustrate the ways in which the Times has led its readers to believe war reflects beauty, love, and God in Christ. Shields’s essay “War is Beautiful, They Said,” concisely articulates the ways in which the Times has taken the place of the WWI-era citizens who encouraged their youth to fight with the phrase “Dulce et decorum est.”

Fusion of Church & State

As a result of his experiences with war, Owen questioned and challenged religion, as is evident in some of his poetry. When the language of self-sacrifice and larger purpose is used by both religion and country, it is easy to equate the call to die for one’s country with the call “to die for one’s friends,” as one oft-misused scriptural verse says. When a soldier realizes that his country’s values have betrayed him, the feeling of betrayal is extended to the religion whose vocabulary and imagery the political leaders utilized. When the vocabulary of the State is the same as the vocabulary of the Church, and when the church quietly acquiesces to such misuse, betrayal by one is equal to betrayal by the other.

In his work, Shields curates a visual argument for the ways in which religious “visual vocabulary” is utilized to incite young Americans to war, or at least to encourage Americans to support the war (or perhaps, at the very least, to stop Americans from actively protesting the war). Shields suggests that in the Times, the imagery of the Church has been coopted for the purposes of the State.

The separation of Church and State is sometimes lamented as a problem in USAmerican society, but history can show us that the separation is for the purposes of protecting the integrity of the Church as much or more so than it is to protect the State. In Shields’s work, we see the modern-day effects of the fusion of these two institutions, making visible — behind the beauty — the death and degradation that come at the manipulation of religious symbols for political purposes.

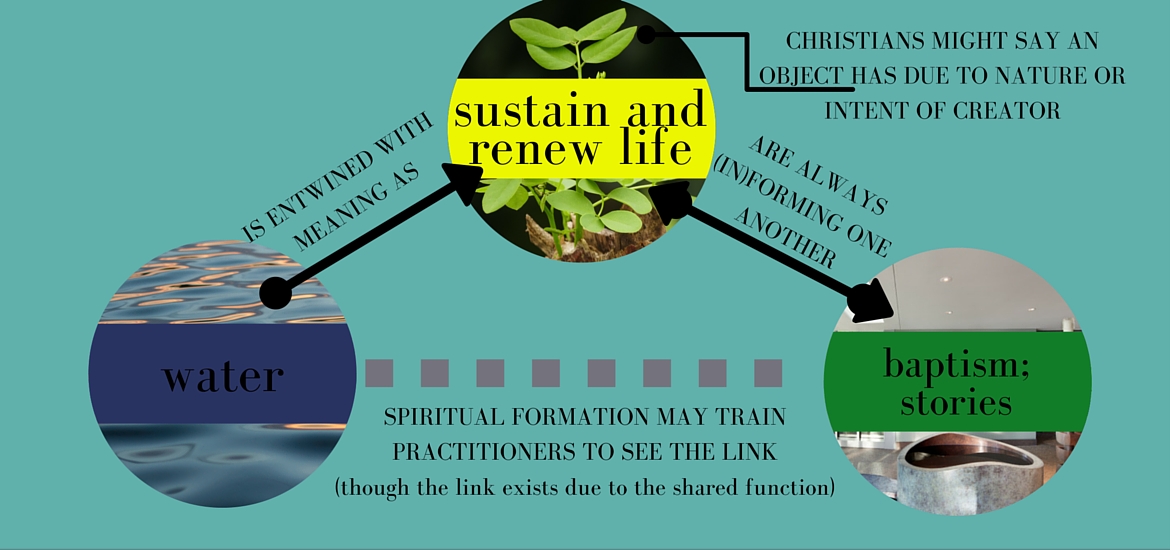

God

On his section of photographs he places under the theme of “God,” Shields writes that “the Times uses its front-page war photographs to convey that a chaotic world is ultimately under control” (WiB p 9). The photos in this section, to my perception, fall in two categories.

The first: aerial shots. Obama (representative of American power) helicoptering over a city; a soldier (his face obscured so as to represent all soldiers, or perhaps American might) aiming a gun out of an aircraft.

Symbols of power that hover over a city, look over a city — benevolently or malevolently? in protection or battle? The same questions could be asked of these troops as we ask of God.

The second category: Middle Eastern people subjugating themselves — one man is nearly nude, on his knees in front of soldiers’ legs; another is kissing the hand of a soldier as one would a revered priest. They’re subjugating themselves before soldiers whose faces are always averted from the camera or out of shot; again, they could be any soldier, they are there to represent not an individual but a symbol.

The visual signs of prostration and reverence — traditionally religious symbols — are here applied to political and military might in a way that, as Shields theme title suggests, equates American forces with God.

Pieta

Another section is titled “Pieta,” which is a subject in Christian art that depicts the Virgin Mary cradling Jesus, recently dead and removed from the cross.

To summarize this theme, Shields write a succinct equation to illustrate the understanding of the Times: “War death = Christ’s death on the cross. The process of removing the body from the cross and battlefield is sacred” (WiB p 9). The images are solemn beauty; the overtones of sacrifice are palpable.

Beauty / Self-Sacrifice

Shields titles this theme simply “Beauty.” He summarizes the section as “portraits of the other…mostly women and children, beauties seeking salvation. Male sacrifice is consecrated in these faces — [they are] the rationale for going to war” (WiB p 9).

His description makes clear that this understanding of beauty is connected to self-sacrifice for the sake of a common good, or self-sacrifice for the good of another — which is, of course, one way that Christians understand Jesus on the cross (or, more accurately, the singular way in which many USAmerican Christians understand the cross).

The cameras focus on women and children, clear-eyed and suffering, often surrounded by blood or fire. They are sometimes looking into the camera as though salvation from these surroundings lies with us, the American viewer; as if their salvation is dependent upon our support of this war’s continuation.

Differentiation and Memorial Day

Whatever you believe about the political realities or necessities behind the war, I think we can recognize that the daily reality of the war experience contains layers of horror. Even for those who manage to escape physically unharmed (though, arguably, the levels of stress-induced hormones that flood the brains of our soldiers in their formative years means that it’s near impossible to have no physical impact; in a very real sense, no one leaves unharmed) — but even for those who manage to come home physically intact, there is real pain involved: the emotional pain of losing peers, the trauma of living amidst death, the survivor’s guilt.

I know many Christians view war as a necessary evil in our world. Perhaps they’re right. But even so, Shields’s work suggests to me that for Christians to allow the political powers to use our imagery and symbols is to allow the State to displace the Church. To quietly allow the State to serve Death using the symbols that are meant for Life is a betrayal of the gospel.

If war is a necessary evil for the State, let us keep the Church intact so that those who come home from war still have safe place in society, a place that has not betrayed them.

Christ was meant to be the last sacrifice. To glorify soldiers as sacrifices for our society only calls us back to the cross, to a recognition of the two millennia that have passed in which we have failed to construct a society that recognizes Christ as the final sacrifice. Perhaps not only on Memorial Day, but every day, we can honor the soldiers who gave their lives by working for peace, by constructing a society which no longer demands their sacrifice.

Until that day, may we not only remember the soldiers who gave their lives, but also witness to our returning veterans — not only in their triumphs, but in their loss and grief.

May we free them from being anonymous symbols of power on our newspapers in order that they might become wholly human in all beauty and brokenness.

May we help work alongside them to re-connect to the goodness, light, and life that is in the world and in our hearts and theirs.

May we listen and witness to whatever shards of their experiences they’re able and willing to entrust to us, and may we do so as faithfully, attentively, and gently as we witness the breaking of the bread.

To never miss a post (and to gain access to the free, ever-expanding library of resources to help you engage culture in ways that deepen your faith), sign up to get each week’s blog posts to your inbox: