“Staying together is more important than how we stay together.”

In Captain America: Civil War, Natasha Romanoff / Black Widow says this to Steve Rogers / Captain America. It’s her attempt to keep him from leaving the Avengers, from dividing the Avengers into factions.

Romanoff puts their togetherness above all else. She believes that unity is more important than differences. She believes that what they gain from collaboration is more important than any regulations on that collaboration.

Romanoff is willing to have these hard conversations. She’s willing to engage the variety of beliefs. And she’s willing to mediate between these sad and stubborn men for the sake of “staying together.”

Rogers, of course, disagrees. We knew he would. It wouldn’t be much of a superhero movie if Romanoff’s heartfelt interventions with Rogers and Stark were heard and responded to in a mature and reasonable manner.

Rogers reveals his priority in his response to Romanoff: “What are we giving up to do it?”

He’s focused on what they would each lose in order to stay together. Rogers believes liberty matters more than unity. He believes that freedom to live his personal ideals is greater than collaboration.

I love that this conversation is set in a church.

Because this conversation is always happening in the Church.

Following the memorial service, Romanoff and Rogers are alone in the sanctuary when they have this conversation.

I love it because the debate between unity and liberty is the conversation that’s taken place — continues to take place — in the long narrative of church history.

We’re always debating how to maintain unity while trying to discern and follow the movement of the Spirit.

The trick is that the movement of change looks like an improvement and progress to some. Like it does to Stark in the movie. And at the same time, it feels constrictive and dangerous to others. Like it does to Rogers.

How do we discern what’s true? How do we discern what the Spirit wants? How do we discern the balance between unity and freedom when we hear the Spirit differently?

For instance: The Episcopal Church (the USA branch of the Anglican church) was in conversations around the ordination of women to the priesthood. The sentiment was that we couldn’t do it until we all did it together. At least, it was until a few bishops, in very Captain America fashion, gathered and ordained women, forcing the conversation — and the church — to come up with a different action. They felt that what we were giving up for the sake of unity (namely, women’s voices in church leadership) wasn’t worth the cost.

The Church of England had a different answer: they valued unity above all, and so went much slower. Nearly 20 years slower in ordaining women to the priesthood. But they managed to go through that shift with less division.

Right now, many denominations are in the midst of similar debates.

The United Methodist Church, right now, is in the midst of this debate. The Western Division elected a lesbian as their bishop in a claim for liberty — and in defiance of church rules. Now the wider United Methodist Church needs to decide: Will they value liberty or unity?

I’m not sure if I’m devoted entirely to liberty or to unity. There’s a part of me that wants to cheer the UMC Western Division for boldly following the Spirit and standing for love and justice. And there’s part of me that feels the sadness of possible division. That wants to take hands with those who don’t agree or don’t understand and help them take just the next step toward acceptance. That wants to help people stay together as much as possible.

In Captain America: Civil War, the narrative “wants” us to side with Rogers’ ideals.

We hear this in Sharon Carter’s eulogy of her aunt, right before the conversation between Romanoff and Rogers:

[Margaret Carter] said, compromise when you can. When you can’t, don’t. Even if everyone is telling you that something wrong is something right. Even if the whole world is telling you to move. It is your duty, to plant yourself like a tree, look them in they eye and say, ” No…you move.”

The main piece of Margaret Carter’s advice here was “compromise when you can.” And yet Sharon manages to take the nuance, the exception to the rule, and to transform it into the central piece of advice. I doubt this was Margaret’s emphasis — she sounds more like Romanoff in her initial advice to compromise. Her advice is a call for unity. Sharon adds the emphasis in order to give a message to Rogers — and to move the narrative (and the audience) into more sympathy for the team liberty.

I had hoped that Stark and Rogers would move towards one another in the compromise that Margaret (via Sharon) calls for. That they would enter into the messy tension of unity and liberty and figure out a way they can be together and not feel constrained in the process.

Alas, I hope for the Kingdom.

By the end of the movie, the writers believe they’ve swayed us far enough to team Captain America that it’s okay for Rogers to perform a jail break and that we’ll be … if not happy about it, at least tolerant of it.

But I was disappointed. Rogers strikes me as reckless and individualistic, refusing to see the problems of his actions in a larger system. His actions are congruent with his own values, but he can’t see past his own values to understand his actions’ impact on others or to understand the way his actions function in a larger system.

Which could be seen as the criticism of the movie: Captain America is a stand-in for USAmerica. And Rogers is how the rest of the world, perhaps, views us: as a nation that lives our own values and ideals, imposing them on the world without care what other people or groups they hurt, because freedom and capitalism.

Back to the fact that the unity-or-liberty conversation happens in a church:

You only need to glance at a list of denominations in USAmerica to know that divisive idealism can’t be the direction we continue to follow. We continue to fracture and split the Church, and each time we do, an appendage of the Body of Christ is amputated. Such individualism and divisiveness should be a cause of lament, not rejoicing.

And that’s what I felt when I saw the empty cells of the Avengers’ prison. Not rejoicing in their freedom, but deep sadness at an action that would further fracture the Avengers, their relationship with UN, and their relationship with the global community.

In the comments…

Which do you, personally, tend to value more: unity or individual liberty?

Which does your family value more? your community? your parish? your denomination?

How does that value manifest?

For posts delivered to your inbox and access to the Free, Ever-Expanding Library, sign up below:

Sin pits broken people against one another, when the very thing they need could be found by more deeply understanding the soul within the body they’re pummeling.

Sin pits broken people against one another, when the very thing they need could be found by more deeply understanding the soul within the body they’re pummeling.

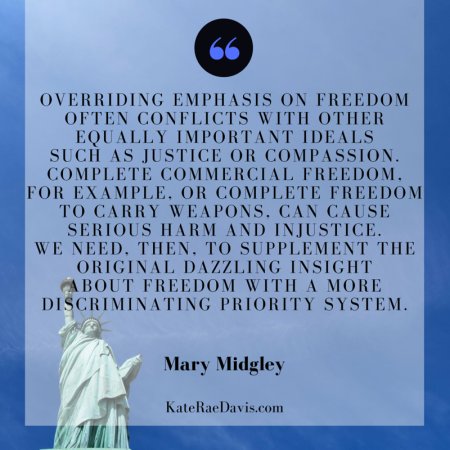

I should note that Midgley is English, though the issues she raises in this paragraph are particular relevant to contemporary USAmerica. Unchecked capitalism and weapon-carrying are two freedoms that USAmericans seem to value more than other developed countries.

I should note that Midgley is English, though the issues she raises in this paragraph are particular relevant to contemporary USAmerica. Unchecked capitalism and weapon-carrying are two freedoms that USAmericans seem to value more than other developed countries.