This sermon was written for Evergreen Mennonite Church in Kirkland, Washington. The primary text was Psalm 51; referenced texts are 2 Samuel 11-12 and Philippians 2:5-11.

Before he was King of Israel, David was a shepherd boy. He was the youngest of eight sons; when he wasn’t doing the very unroyal work of tending sheep, I imagine he was picked on by his older brothers. And then, one day, an old man shows up and names him King. He was just an ordinary guy, more or less content with his position in life — then suddenly holds the responsibility of a Kingdom. David rises to the challenge in relationship, in military strength, in religious commitment — he is not only a good leader, he’s a good person, described as “a man after God’s own heart.”

Until one afternoon when David saw her bathing on the roof and her beauty overthrew him. Now, David knew how to keep his head about him. When confronted with the well-shielded, well-armed giant Goliath, he remained cool enough to lethally aim a pebble. We wouldn’t expect this man to commit a sin of fiery passion — yet he does.

Afterwards, in his guilt, he tries to cover his sin by sending Bathsheba’s husband to the front line of battle. All his life, David had worked consistently to bring about the Kingdom of God — conquering Jerusalem, naming it his capital, vowing to build a temple there. He’s the last person we would expect to order the slaying of one of his own men, the last person we would expect to commit a sin of cold calculation — yet he does.

We have, in our cultural collective, a certain types. We say things like “He’s the type of person who would give you the shirt off his back” or “She’s the type of person who would sell her own mother to make a buck.” We have similar types of people for the kind of person who commits adultery, or the kind of person who commits murder. David, we might say, doesn’t fit the type — yet he sins.

Which is why I sometimes hear this description of David: “He was one of Israel’s greatest Kings, except for that Bathsheba business.” But I take some comfort in “that Bathsheba business,” find solace in the fact that David fell into such terrible and — let’s just say it — such obvious sin.

I take comfort because David seems, on the surface, to be the exemplary person who has his life together. Scripture tells us that he’s handsome. He’s an intelligent strategist. A strong warrior. He’s King of the Chosen People of God. He has absolutely everything by which we would mark success — the title, the house, the body, the wealth, the respect. The strong prayer life, commitment to God. And yet his sins here reveal that he doesn’t have it all together — they show that he’s as human as I am.

David is a person committed to God. David exploits his power in order to fulfill desire; David exploits his power in order to conspire a murder. In all of this, David shares our humanity.

The King and I seem to have little in common. We’re certainly separated by three thousand years of time and half a globe of distance. We’re separated by culture, social status, power, authority, privilege, and gender. And yet, to fail to read David’s humanity as intimately linked to mine denies the ways in which, on my best days, I am just like him — beautifully and brokenly human. Caught up in sins of passion, conspiring in sins of calculation. Exploiting the power and privilege I do hold.

For although I am not royalty, but I do have power and agency in my own small domains, as we all do in our jobs, our friendships, and our family systems. I have the power to treat others with dignity and respect. Power to exploit or manipulate others for my own ends. Power to ignore others as though they don’t carry the image of God.

* * *

It’s an oft-spoken saying that preachers should have a bible in one hand and a newspaper in the other, and it was in reading the news these last few weeks that I began to see the gift offered us in David’s psalm. For what makes David a great leader isn’t the military strategy or the political savvy, it’s this moment, this psalm. What makes David a great person is the ability to see his actions as wrong, to admit to that wrongdoing, that sin, and to move toward reconciliation. What makes David a great leader is that he confesses his sin as publicly as the sin was made, that he sees his personal actions as intricately tied to the national systems.

I mentioned that I only began to recognize this modeling as a gift when I put my bible in one hand and my newspaper in the other. As I read about the act of terrorism at Mother Emanuel Church in Charleston; as I read about the following acts of terrorism in burning black churches throughout the US South; as I read the countless tweets, facebook updates, blog posts, and journal pieces of African American people begging our nation to collectively realize we have a race problem — David’s psalm became such a gift.

In the same way David doesn’t seem to fit the type, we don’t seem to fit the type either for this sin of racism. Most people don’t identify as racist — even White Pride groups say they aren’t racist, they just love their heritage. And if even they don’t admit racism — what are the chances that the average American will? What are the chances that a people concerned with matters of social justice will recognize their own racist tendencies?

And when I look at the people gathered here — well, I doubt any of you are donning white sheets and setting fire to the lawns and churches of your black neighbors. There are no confederate flags among us, on our cars or our clothing. We just don’t fit the type of person who is racist.

So David’s story gives me pause. David doesn’t fit the type of person who would be an adulterer or a murderer. Before Nathan came to him, I don’t believe David thought of himself as an adulterer and murderer. But when confronted, he responds: “Have mercy on me, O God…blot out on my transgressions. Wash me thoroughly from my iniquity, cleanse me from my sin. For I know my transgressions, my sin is ever before me.”

This confession is part of our holy scripture; it was public in the kingdom in which David reigned. Because he held public office, as it were, his sins were publicly known — people talk. And in his psalm, he models for us what repentance looks like by showing the way in which true confession is AS public as the sin. For him, the people likely all knew or had heard whisperings; his confession had to be public.

For us it is likely smaller. I recently read a piece about race in Seattle. The reporter, in researching, wrote that she had approached a young African American man and told him, “I’d love to interview you; you’re so eloquent,” and then immediately hears herself sound, in her words, “like one of those people who said candidate Obama was so well-behaved, well-groomed, polite — for a black man.”

She could have just gone on with the interview. She could have caught herself in her head, confessed to God (privately), and said nothing to the man. He would have answered her interview questions, probably eloquently; she would have gotten her quotes for the story; no real harm done. Just her lingering feeling of self-consciousness after using a word with a history and his lingering feeling of needing to perform for white people to notice to him.

Instead, the reporter quickly confesses to the man: “I can’t believe I just called you eloquent.” He gives her a knowing look, and then begins to laugh, a bubbling outpour of grace, and she is freed to join in his laughter — the reconciliation complete in laughter’s grace. And they carry on with an interview that, I imagine, was somehow more comfortable and authentic than it would have been had she refused to confess her sin as publicly as it had been made.

So, a confession of my own: I have, this week even, chosen a different route to walk because I saw a black man ahead of me; I am a racist.

Another confession: I am a white person talking about race, and I am very uncomfortable. This discomfort and unwillingness to talk about race is part of what makes me racist. And part of what makes me privileged; white people get to choose whether or not we discuss race.

Another confession: I’m only able to speak in this room, at this time, because education systems have privileged me — at least in part — because of my race.

I confess these sins; the reporter confesses her sin; David confesses his sin because the recognition of sin as sin and the appropriate confession of it are not only the first steps toward reconciliation, they are the direct cause of reconciliation.

I’m encouraged to confess my sins and to name my iniquities, because David does the same for sins that are, if we were to use a measuring stick (which we aren’t supposed to do, but if we were to), David’s sins would be “worse.” Adultery. Murder. And yet David is restored to God; it seems that nothing is beyond God’s capacity and willingness to forgive, even when justice cannot be served. David is restored to the community and reconciled to God even though Bathsheba’s marriage and Uriah’s life cannot be restored. God’s forgiveness of David is so complete that God blesses the union of David and Bathsheba in the form of their son Solomon — the wisest of all Israel’s kings. In a sense, we could say that wisdom is the result of confession.

That David is reconciled even though justice cannot be done — this lends me tremendous hope for the possibility of racial reconciliation. It will not be easy. It will require recognizing personal acts as sinful. It will require looking at national systems as sinful. It will require true confession and repentance. It will require a breaking open and cutting away of the callouses around our hearts, will require, as David says, brokenheartedness. David says “A broken heart, O God, you will not despise.” Today we might say, “A soft heart, O God, you will not despise.” It was modeled for us in Christ, who emptied himself, who refused to exploit his power so that he could be with us in our humanity and our suffering.

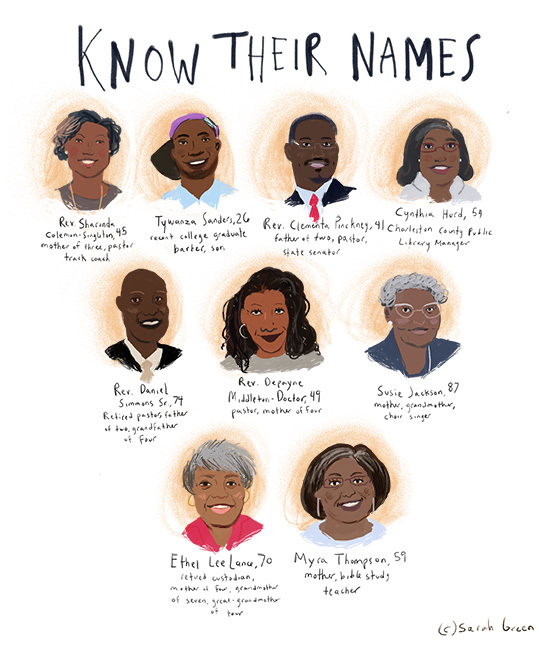

When it comes to racism in America, justice cannot be served this side of the coming of God’s Kingdom. We cannot undo slavery. We cannot reclaim the four million or more lives that were lost in crossing the Atlantic in cargo holds. We cannot bring back Trayvon Martin, or Michael Brown, or Eric Garner. We cannot bring back the nine victims of Mother Emanuel Church– Sharonda, Clementa, Cynthia, Tywanza, Myra, Ethel, Daniel, Depayne, Susie.

Have mercy on us, O God,

according to your steadfast love;

according to your abundant mercy

blot out our transgressions.

Wash us thoroughly from our iniquities,

and cleanse us from our sin.

For we are learning to know our transgressions,

and our sin is ever before us.

Indeed, we were born guilty,

sinners when our mothers conceived us.

Let us hear joy and gladness;

let the bones that have been crushed rejoice.

Create in us clean hearts, O God,

and put a new and right spirit within us.

Sustain in us a willing spirit.

Then we will teach transgressors your ways,

and sinners will return to you.

Deliver us from bloodshed, O God,

O God of our salvation,

and our tongue will sing aloud of your deliverance.

You have no delight in sacrifice;

if we were to give a burnt offering, you would not be pleased.

The sacrifice acceptable to God is a broken spirit;

a broken and contrite heart, O God, you will not despise.