I was recently told that my work offends non-Christian artists. In books or movies, I see images of incarnation, baptism, eucharist, crucifixion. Or, I see parallels between this narrative and the narratives that are found in scripture. Or, I see parallels between this character or person and aspects of Christ’s identity. I see Christian symbols everywhere. A reader told me that it’s inappropriate to have these Christian understandings of secular art, that it may be offensive to the non-religious artists who create these narratives.

Which is hard to hear, because I see God speaking everywhere. The symbols and narratives from Christian scripture are still very much at play in our world. The human condition hasn’t changed; the scriptures are still very much relevant; it is only on the surface that our situation appears to have shifted.

To help clarify my understanding of Christian symbols in narratives, this post is the beginning of a series on symbol and metaphor in culture and Christianity. Since this is the work that lays bear the structure for my posts on culture, I’m calling them “Foundations” posts; you can click the Foundations category to see them all.

In this post, I’m going to cover the origin of symbol and ritual. Next time, I’ll dive into a particularly Christian understanding of how symbol and ritual function. Eventually, we’ll cover a variety of Christian symbols and how they are at work in cultural narratives.

It’s Elementary

Part of the reason similar symbols are found in both Christian narratives and “secular” narratives is because of the essential, elemental nature of symbols. The basic elements of human living are consistent across space and time. We all have more or less similar body structures, composed of similar substances, that act in similar movements. We each have breath and air, we each have a relationship with water (which comprises the majority of our bodies) and with fire (even if that fire is just in the sun). It is precisely because these things are so essential to our lives that they become the center for many symbols: body parts (eyes/sight, ears/hearing, feet/transportation, etc.), air, water, fire.

Landscapes and their flora are also commonly used symbols. Due to physical locatedness, landscapes may not seem to be immediately ready for broad use, but though we may not have experience with a landscape, we are able to imagine ourselves into it. For instance, I live in Seattle, the Emerald City, but when a friend says he’s going through a spiritual desert, there’s no need for explanation. Similarly, animals, for all their great global variety, are common symbols: it seems that humans don’t associate earthworms with peace and freedom, just as we’ve not looked at a lion and thought of death and decay.

The physical structures of human living are generally consistent across time, space, and culture. And so what we humans use for symbols are these same fundamental materials of our human lives. It is not coincidence; it is precisely why these objects become symbols.

Material Objects Hold Spiritual Truths

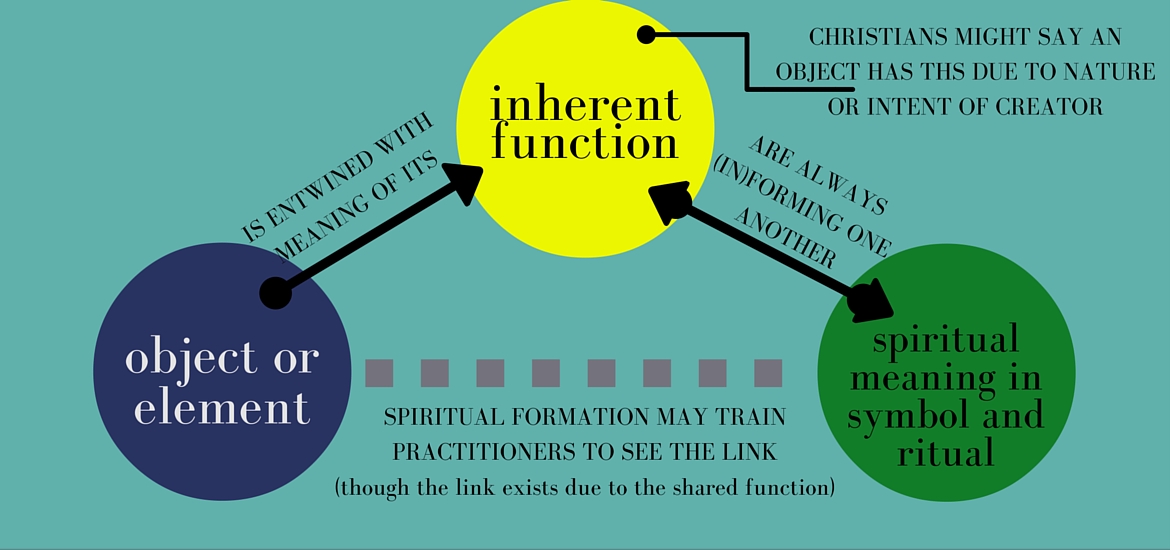

The essence of a symbol exists the way it does because it is the essence of that object’s function in the real world.

To begin: there is a real world Object, which has a certain type of Function. The Object becomes associated with the Function. That Function is external and real in the world, but people notice that it connects to an internal reality as well — the Function is in some way real and present in the internal experience. People begin to use the Object to represent the internal reality that feels similar to the Function — the Object has now become a Symbol.

If that use of the Object as that Symbol connects with other people, it becomes a community Ritual that externally conveys collective inner realities. The material and the spiritual are now held together in the Object-Symbol; just as the Ritual utilizes the Object’s original Function, the presence of the Object may conjure the experiences and meaning of the Ritual.

In various communities, the Object may represent various Symbols and/or become the center of various Rituals, though these various uses still point back to aspects of the original Function. The Object and the Function are always singular, no matter how plural the Symbols and Rituals derived from them are. The Symbols and Rituals always point back to the initial, natural way of things. But: the Rituals shift, and the Symbol may take on new meanings as a result.

Over time, the Object-Symbol has added texture and heritage from its use in these Rituals, which means that the Symbol can be used in ways that add to, remix, even violate those Rituals in order to create new Rituals that convey new layers of internal realities — new Symbols. So when the Object is referred to in a narrative, it is important to understand what the culture understands the meaning of that Object-Symbol and how that Object-Symbol interacts with other Object-Symbols in the story.

This is getting hard to handle. Let’s use an example.

An Example

Water Becomes Symbol

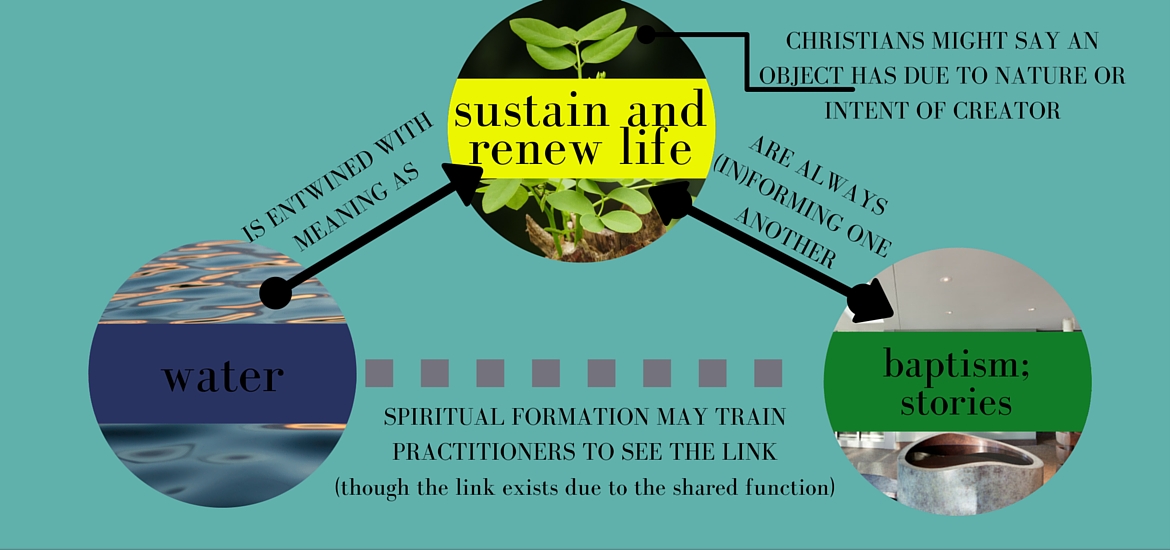

For this example, water will be our Object. It’s an easy symbol in that it’s all over the place, but also somewhat difficult for the same reason — there are many forms that water can come in (oceans, rivers, lakes, wells, bubbles, showers, baths, floods, tsunamis) and there’s an heritage associated with each form, giving the symbol a lot of texture. For the sake of this post, I’m discussing water in a rather general and benign way (we’ll deal with the variations of salt and destruction and temperature another time, as they tend to be remixes on the core Symbol).

Water has a certain type of Function in the world, and did before it became a symbol, before language was a human technology, before humans walked the earth. The Function is this: Water sustains life. That was true in the beginning, is true now, and will always be true.

At some early point in human history, people noticed that wherever there’s water, there are living things; where there’s much water, there’s an abundance of green and moving creatures. And the inverse is also true: where there is little water, there is little green and fewer creatures. People noticed that, in order to revive a plant, animal, or person, water was necessary. I imagine there were times when the fields were withering with brown plants, and then rain came and gave the field new life. I imagine there were times when a traveler had gotten lost in the desert and was hallucinatory and weak, but after being given water, he was revitalized (a word that literally means “to give life again”).

Notice: at this point, this language is not symbolic. It is simply describing reality. It is describing what literally happens when water is present.

It would have only been later, after these observations about life’s ability to renew, refresh, and revitalize, that someone would have thought, I know what that feels like. I have known in my soul what it feels like to be dry, and then something comes along and I feel like I have been given life again. Perhaps people started saying to their friends, “Some part of my inner world has been in a desert, but has just found a well of fresh water.” Now, the Object (water) and its Function (revitalization) are being used to describe an internal reality – water has become a Symbol.

Water Becomes Ritual

We can say with some certainty that using water to describe an internal experience was a symbol that connected with others, because we know it became Ritual.

In parts of ancient Egypt, the dead were submerged into the cold water of the Nile to convey that, though their life as it had been known was gone, in some way they will experience a new life. Entrance into the ancient Egyptian cult of Isis required a ritual of submersion into water as an outward sign to symbolize that an internal new life was beginning. In these rituals, the material use of water became tied to the spiritual experience of revitalization.

For the Jewish people, water was used for the washing of bodies and clothes as a sign of purification (“purity” itself being an abstraction of concepts related to life and wellness). In a community where the scriptural texts were memorized, such use of water would likely conjure memories of the Jewish community’s heritage with the symbol. People might remember “the Spirit of God who hovers over the waters” before the creation of life (Genesis 1). They might remember Moses leading God’s people out of slavery in Egypt, through the parted waters of the Red Sea, and into new life as a free people (Exodus 14).

In the beginning of the Christian era, Jewish communities adopted the custom of submerging converts: seven days after circumcision, the convert would be submerged, naked, in a pool of flowing water and would rise as a “son of Israel” (the familial language of “son” ties the practice to “birth” and, thus, to new life).

Notice that different groups utilized the water ritual with great variety. The submersions — called baptisms long before the holy dunking of Jesus — used various types or bodies of water, each with their own particular narrative. Some groups submerged the living, others the dead. Some groups submerged entire bodies, some only parts. Some groups baptized the clothed; for others, nudity was a requirement.

Yet despite the many differences in these rituals, the Symbol of water remains singular, and water’s Function as a provider of new life can be easily traced throughout the Rituals. The use of the Symbol in narrative and in Ritual varies, but it always points back to the original, pre-symbol Function.

Next Time

We’ve covered how an object becomes a symbol and looked at how this occurred with the example of water — but only up to before Jesus’s life. In the next Foundations post, we’ll look at how Jesus remixes the water symbol and how the Christian community ritualizes that remixing. Then we’ll look at a couple of instances of the water symbol’s use in contemporary culture and tie it all together to explain why Christians see baptism in the “secular.”