What relationship do you mean to evoke when you say “God”?

I don’t think any of us mean the bearded old guy on a cloud. At last not on purpose.

We’ve moved away from rulership metaphors, for the most part. Which makes sense. “King” and “Lord” don’t carry a lot of metaphorical weight with people who elect their political leadership.

Many Christians are moving away from the parental imagery of Father (and of Mother, for that matter). Blame it on Freud, but we’re in an age of psychological awareness. As large groups of people work on to articulate the ways in which their parents fall far short of divine behavior, it will continue to get more problematic to evoke parental imagery for God.

So we’re left wondering: how do we understand this divine, invisible, felt force that moves through the cosmos? What metaphor or analogy can we use for something beyond all understanding? What language can we put to something so profoundly experiential?

The Good Gift Giver

I’ve settled on one image that feels right and true: God is the giver of good gifts.

Throughout scripture we read that God gives strength, wisdom, and all that is good. For just a short list, see Psalm 29:11; Psalm 85:12; Proverbs 2:6; Matthew 7:11; James 1:5; James 1:17. That list could be really long. The act of giving is an essential characteristic of God and is made incarnational in Jesus.

Kathryn Tanner writes about God as the giver of good gifts. She recognizes that the God-made-flesh moment is what unites humanity and God. Tanner says that in this uniting work, “God gives everything necessary. … God contributes all the elements. … God gives completely to us.”

Kathryn Tanner writes about God as the giver of good gifts. She recognizes that the God-made-flesh moment is what unites humanity and God. Tanner says that in this uniting work, “God gives everything necessary. … God contributes all the elements. … God gives completely to us.”

Sacrifice is no longer required of humanity. There is nothing to sacrifice. In a great reversal of expectations, God has provided and offered all the elements of sacrifice as a gift to humanity. You could even go so far as to say that it is impossible for us to truly sacrifice to God, for “God needs nothing but wants to give all.” The Christian God is “a God of gift-giving abundance.”

Receiving Gifts

I struggle with this conception of God as the giver of everything.

If God provides every aspect of the sacrifice needed for my atonement, what is left for me to give? It’s not that attending church services or spending time in daily devotions is insufficient, it’s that it’s unnecessary to the atoning project. How do we participate in a relationship if God has done all that needs doing?

I think the first step for us is to recognize the goodness of the gifts.

And then to respond with gracious receptivity and surrender. To offer, as Tanner says, “the return to God of prior gifts on God’s part to us … as an appropriate act of thanksgiving.”

Our response to God’s gifts is to return those gifts for the purpose of God. As Ignatius phrased it in prayer:

Our response to God’s gifts is to return those gifts for the purpose of God. As Ignatius phrased it in prayer:

“Take and receive, Lord, my entire liberty, my memory, my understanding… All that I am and have you have given to me, and I give it all back to you to be disposed of according to your good pleasure.”

Gifts are received and returned to God when we use the gifts to the pleasure of God. I think this takes the form of using the gifts to the service and benefit of humanity (but that’s a topic of its own lengthy post).

There are a thousand examples of gifts being given back in ways to please God. A gift of innovation that is used to restore creation; a gift for joy and laughter that is shared to bring joy to others; a gift for organizing resources used to care for those in need.

Not Receiving Gifts

And then there are ways in which we don’t accept and return God’s gifts.

We refuse rather than receive. We misuse rather than return. That is, we sin.

Sin is shorthand for what keeps us from relationship with God. In this image, sin is shorthand for the ways in which we fail to receive or use God’s good gifts.

Refusing Gifts

We refuse gifts because of blockages.

Perhaps we’re unable to receive because our hands are full of what has been handed from elsewhere.

Perhaps our hands are forcefully closed or our arms will not risk outstretching to receive.

Or we have been handed stones in the past and we won’t risk asking for bread again.

Or we have been socially conditioned to view ourselves as unworthy of good gifts.

We refuse gifts because of blindness.

Perhaps we don’t notice what is offered.

Or perhaps we don’t recognize that the gift is good.

Or we don’t believe it’s freely offered, suspecting hidden strings attached.

Or perhaps we’re distracted.

And in all of this, God remains the giver. Tanner is adamant: the “gift is still being offered even as we turn away from it in sin.”

Misusing Gifts

When we successfully receive a gift, our participation is not done. Sometimes we misuse the gifts that have been given to us.

A gift can be used for purposes other than for what was designed or intended. Like a kid who asks for a water gun that is then used to torment the neighbor girl, sometimes gifts aren’t used as they were intended. Not that I’m speaking from personal experience or anything…

A gift can be used in its right function (the gun shoots water), but for ill purposes (torment instead of fun, surprise instead of consenting play). In a spiritual sense, a gift might be used for ill ends such as personal glory, self-promotion, or financial prosperity rather than for the good of others.

Or, more subtle but perhaps equally sinister is the person who claims that their gifts originate within their own self. The person who refuses to acknowledge that there was any gifting involved.

Or, a gift can be misused through its destruction in inappropriate sacrifice.

Justin Martyr writes: “We have been taught that the only honor that is worthy of [God] is not to consume by fire what he has brought into being for our sustenance, but to use it for ourselves and those who need.”

Martyr’s words remind me of a story of an African man who heard of Jesus’s sacrifice and that no other sacrifices were necessary. So he stopped sacrificing his animals, and was better able to feed his community. He laughed, “Jesus saves…the chickens and the goats!”

The sacrificial misuse of spiritual gifts often occurs through misunderstanding the purpose of gifts. Women, I think, are socially conditioned to destroy what is given. Women with gifts of leadership or prophecy or any number of things are told to “sacrifice” for the sake of being a good wife/mother/Christian. She is being lied to about the essential nature of her sex and about the appropriate use of her gifts.

Systems of Sin

When gifts are refused or misused, we tend to focus on individual choice. Or perhaps we’re generous — we speak in terms of predisposition, family patterns, and circumstances.

But at least as important as the individual is the reality of the wider system.

We all live and move within layers of systems. Often unknowingly, or unquestioningly. Family systems, yes, but also cultural norms, socializations (what is “polite” or “proper”), societal roles. And these systems are influenced by religious teachings, traditions, doctrines, and ways of interpreting scripture. All of these influence how and whether we respond to the gifts of God.

In a systemic sense, we are all complicit in the sins of the individual, because we have created a context in which sin may be a reasonable or beneficial option.

That might sound far-fetched, or like too much guilt. But consider, for instance, the sin of murder: we’ve created a context in which weapons of many sorts are readily available. In the US, we’ve even come up with legal terms we view as sacred: Self Defense. As though the text reads, “Thou shalt not kill, unless in the circumstances that murder is a countermeasure in order to defend the health and well-being of oneself or another.”

We’ve created a context in which murder is reasonable.

And even if we question that norm, we are complicit. At least, I am, every moment that I’m not trying to change the system.

If that feels extreme, consider the sin of theft. We’ve participated in circumstances in which people starve and won’t be fed. This is true even if our participation is through a lack of action to change anything — I haven’t welcomed to my dinner table any young adults who have aged out of the foster system or mentally ill persons with no home to return to. So I’m complicit.

Grace

Madeleine L’Engle:

Madeleine L’Engle:

“It is no coincidence that the root word of whole, health, heal, holy is hale (as in hale and hearty). If we are healed, we become whole; we are hale and hearty; we are holy. The marvelous thing is that this holiness is nothing we can earn. …It is nothing we can do in this do-it-yourself world. It is gift, sheer gift, waiting there to be recognized and received.”

We are each gifted with a seed life that carries the potential to flourish. It is the very fullness of our humanity that is “waiting to be recognized and received.”

Grace is the offering of the seed.

Grace, then, is not an add-on to our human condition. Grace is essential to human nature.

Kathryn Tanner says “humans are created to operate with the gift of God’s grace.” God’s choices are not bound by time, so they’re not sequential. God didn’t create humans and then have to come up with the solution of grace to address the problem of sin.

Instead, God’s choices are wholly formed from the outset. God willed and created humanity to be, at once, sinful and graced. Grace was always part of the design.

Receiving Grace

We receive our identities as “selves-in-relation.” We receive identity from being in relationship with God and neighbor.

For a fully human life, we each must recognize relationship, our own agency to act in the world, and the fact that our agency is tied to relationship. We must recognize that that our abilities are rooted outside our own self-understanding and capacities.

A Christian understanding of identity recognizes that any person’s identity can only be known in part by anyone other than God. This includes recognizing that we each only know our own self in part.

I am more than I can know I am.

We will always be more than we are capable of understanding. Anglican Father Williams explains that faith is the opposite to sin:

“[Faith] consists in the awareness that I am more than I know. …Such faith cannot be contrived. If it were contrivable, if it were something I could create in myself…then it would not be faith. It would be works—my organizing the self I know. That faith can only be the gift of God emphasizes the scandal of our human condition—the scandal of our absolute dependence upon [God]. … This will enable me to assimilate aspects of my being which hitherto I have kept at arm’s length. My awareness of what I am will grow, and the more it grows the less shall I be the slave of sin.“

Faith and grace are deeply related gifts of God. Faith and grace are necessary gifts to receive in order to flourish in our identities.

Roberta Bondi says the early Christians understood grace as “simply God’s help in seeing and knowing the world, ourselves, God, and other people in such a way that love is made possible.”

Roberta Bondi says the early Christians understood grace as “simply God’s help in seeing and knowing the world, ourselves, God, and other people in such a way that love is made possible.”

Fully human selves-in-relation rest in faith and grace. Without faith and grace, a human is less than fully alive — is in sin.

Biblical theologian Mark Biddle writes about this. He says that although “human beings exist only in relationship” and cannot act without risking damage to the relationship, we must also individually develop in order to grow into full personhood. This process of development “is unfortunately rife with opportunities to be stunted by perversion and suppression: sin.”

I had a professor who said it this way: “It is not enough to be a self that is only a self-in-relation.”

In contrast to a graced life of wholeness and holiness is sin. Sin is being less than fully human — being a self that eschews relationship or being a self that is only in relation. Sin blocks human wholeness and holiness through disrupting the cultivation of self. Sin stops human wholeness and holiness through obstructing the cultivation of relationship. Sin disrupts human wholeness and holiness through blocking grace.

This, I believe, is a foundation stone of an understanding of the human condition.

Share in the comments:

What metaphor best describes your relationship to God?

What is your response to understanding God as a gift-giver? How do you think you receive?

To follow the rest of this series, make sure to sign up for once-a-week notifications, right to your inbox. The whole series is available here.

*Kathryn Tanner quotes from Christ the Key, (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2010).

*Justin Martyr, “The First Apology,” trans. Alexander Roberts and James Donaldson, in Alexander Roberts and James Donaldson (eds.), Ante-Nicene Fathers, vol. I, (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1989), 166.

*Madeleine L’Engle, Walking on Water: Reflections on Faith & Art, (Wheaton, IL: H. Shaw, 1980), 60-61.

*Harry Abbott Williams, “Theology and Self-Awareness,” in Soundings: Essays Concerning Christian Understanding, edited by Alexander Roper Vidler, (Cambridge, UK: University Press, 1962), 90.

*Mark E. Biddle, “Sin: Failure to Embrace Authentic Freeodm” in Missing the Mark: Sin and Its Consequences in Biblical Theology, (Nashville, TN: Abindgon, 2005), 66.

*Roberta Bondi, To Love as God Loves: Conversations with the Early Church, (Philadelphia, PA: Fortress Press, 1987), 37.

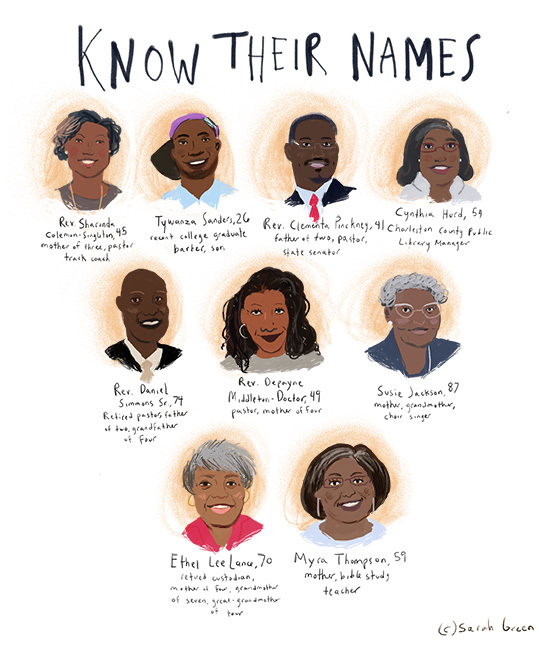

Sin pits broken people against one another, when the very thing they need could be found by more deeply understanding the soul within the body they’re pummeling.

Sin pits broken people against one another, when the very thing they need could be found by more deeply understanding the soul within the body they’re pummeling.

Our church foremothers and forefathers did not develop an understanding of sin so that we could do more sin. The vocabulary of sin is meant to give us sight for the ways we are blocked from participation in love. Understanding

Our church foremothers and forefathers did not develop an understanding of sin so that we could do more sin. The vocabulary of sin is meant to give us sight for the ways we are blocked from participation in love. Understanding

Whenever salvation or grace is preached, what is implicit is the notion of salvation from a state of being, or grace with regards to a tendency. The word ‘sin’ may not be used, but its presence is assumed when we use the words like salvation, redemption, and grace.

Whenever salvation or grace is preached, what is implicit is the notion of salvation from a state of being, or grace with regards to a tendency. The word ‘sin’ may not be used, but its presence is assumed when we use the words like salvation, redemption, and grace. It is not enough to be converted to a new way of life once. We must be converted freshly every day – at times it feels we must be converted every hour – and continuously re-oriented toward the goal. The goal, by the way, is love of God and neighbor.

It is not enough to be converted to a new way of life once. We must be converted freshly every day – at times it feels we must be converted every hour – and continuously re-oriented toward the goal. The goal, by the way, is love of God and neighbor.

Kathryn Tanner writes about God as the giver of good gifts. She recognizes that the God-made-flesh moment is what unites humanity and God. Tanner says that in this uniting work, “God gives everything necessary. … God contributes all the elements. … God gives completely to us.”

Kathryn Tanner writes about God as the giver of good gifts. She recognizes that the God-made-flesh moment is what unites humanity and God. Tanner says that in this uniting work, “God gives everything necessary. … God contributes all the elements. … God gives completely to us.” Our response to God’s gifts is to return those gifts for the purpose of God. As Ignatius phrased it in prayer:

Our response to God’s gifts is to return those gifts for the purpose of God. As Ignatius phrased it in prayer: Madeleine L’Engle:

Madeleine L’Engle: Roberta Bondi says the early Christians understood grace as “simply God’s help in seeing and knowing the world, ourselves, God, and other people in such a way that love is made possible.”

Roberta Bondi says the early Christians understood grace as “simply God’s help in seeing and knowing the world, ourselves, God, and other people in such a way that love is made possible.”